Highlighting standout female leaders who advanced the American conservation movements

Theodore Roosevelt, Aldo Leopold, and John Muir are readily recited by many as the forefathers of the American conservation movement. And though their immense influence is something to be proud of, we’d like to recognize the often-overlooked women whose dedication has helped to shape the modern conservation landscape. Here are eight standouts.

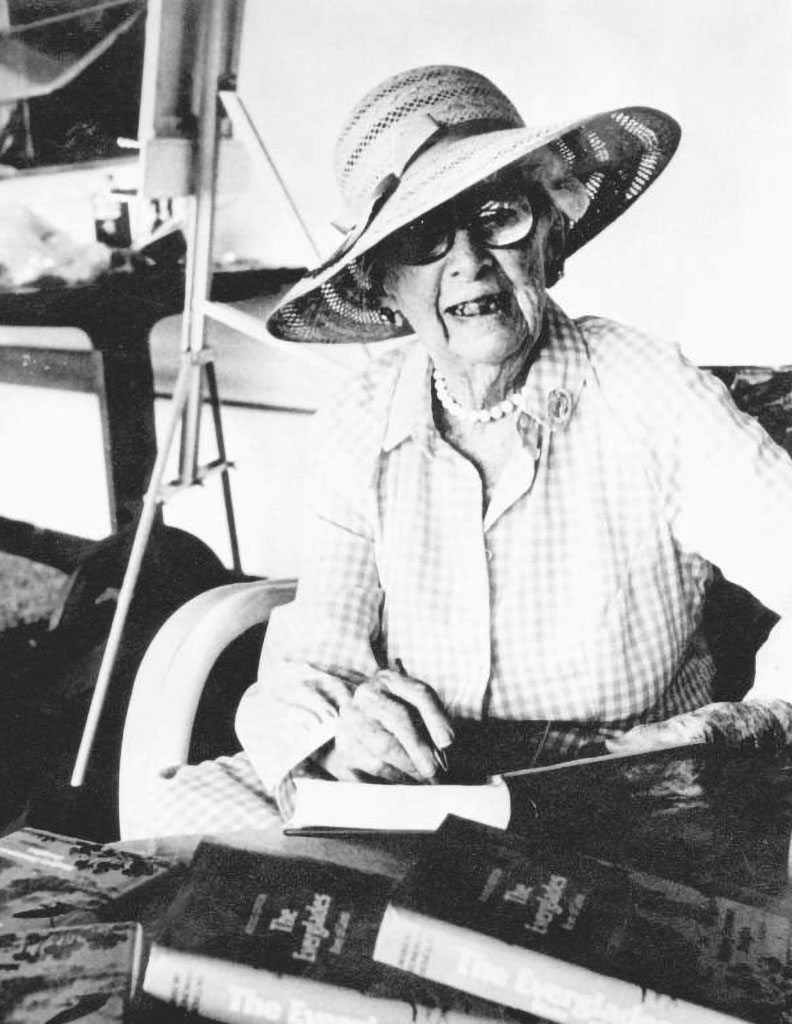

Marjory Stoneman Douglas

Long before water quality in the Everglades was the subject of national news, a young society columnist by the name of Marjory Stoneman Douglas spearheaded a grassroots effort to protect Florida’s sawgrass swamps from being drained and developed. Her extensive research, and the publication of her book “The Everglades: The River of Grass”, changed public perception of this important habitat and led to the creation of Everglades National Park in 1947.

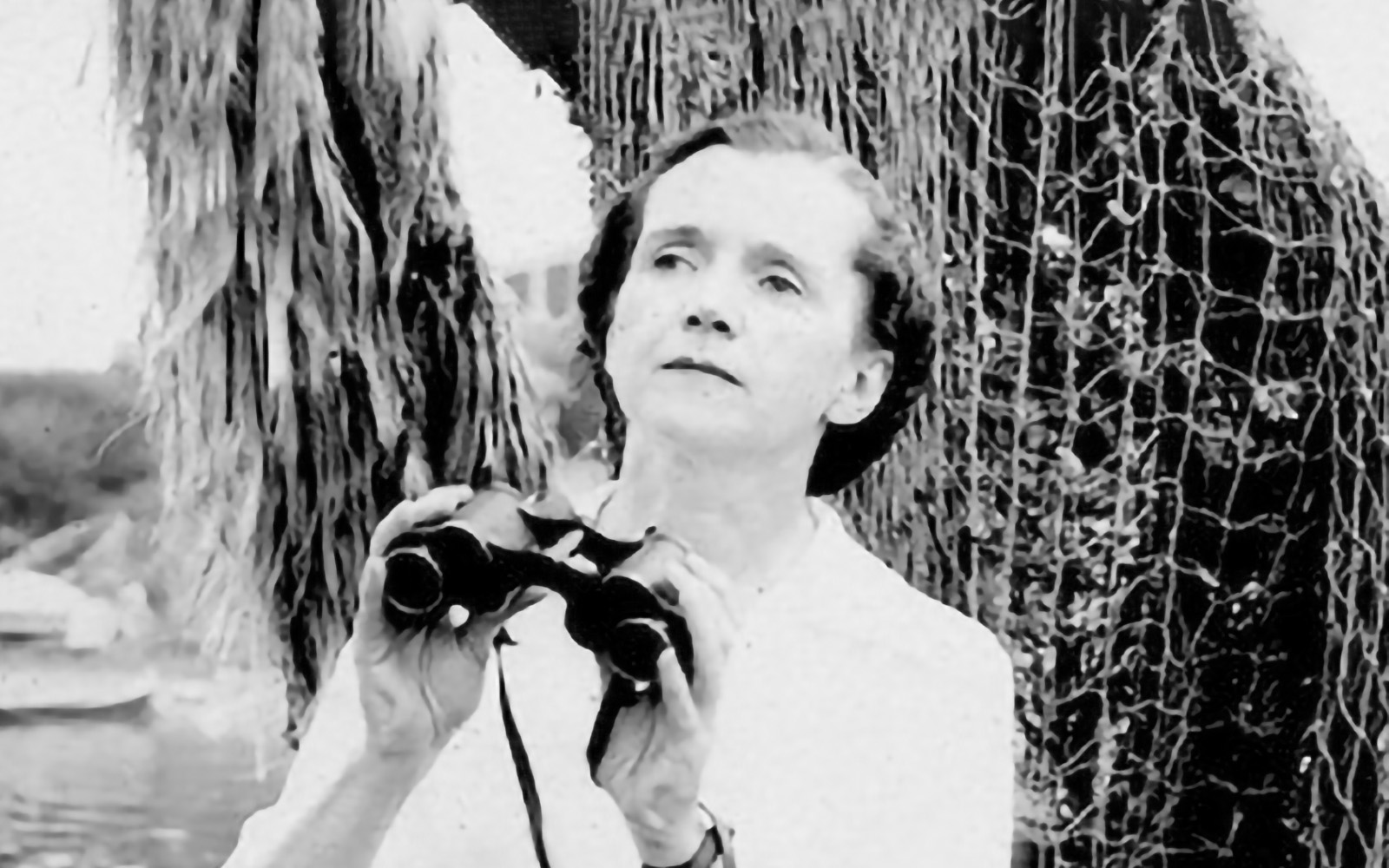

Margaret Murie

Dubbed the “Grandmother of the Conservation Movement,” Margaret “Mardy” Murie’s activism led to the passage of the Wilderness Act. A trailblazer and writer, Murie grew up in Fairbanks, Alaska, and later went on to become the first female graduate of the University of Alaska. Together with her husband, she made several trips into the Artic—the result of which was her book, “Two in the Far North”, a compelling personal account of her lifelong love of Alaska and a testimonial for the preservation of its wilderness.

Although life would eventually lead her away from the state, she never lost her love of its wild places. She organized the coalition that persuaded President Dwight D. Eisenhower to set aside 8 million acres of wilderness as the Arctic National Wildlife Range, which was later expanded and dubbed the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Rachel Carson

Carson began her career as an aquatic biologist writing radio scripts for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries and eventually rose to become editor-in-chief of all publications for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In 1962, she published her seminal work “Silent Spring”, which brought widespread attention to the effects of dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, an insecticide more commonly known as DDT, on bird populations. The public outcry that followed led to stricter regulations on chemical use in the environment, and Carson has since been credited with helping to launch the environmental movement.

Sylvia Earle

Dr. Sylvia Earle is an oceanographer, aquanaut, author, and the first female to serve as chief scientist of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the federal agency responsible for fisheries management and coastal restoration, among other things. After developing a love for scuba diving in college, Earle went on to specialize in botany, believing that an understanding of marine plant life would be integral to ecosystem preservation.

As founder of Mission Blue, a global coalition to improve ocean protection measures and restore the world’s marine ecosystems, Earle utilizes the power of modern media to inform the public and decision-makers about the effects of overfishing, pollution, and climate change while advocating for habitat protection and restoration.

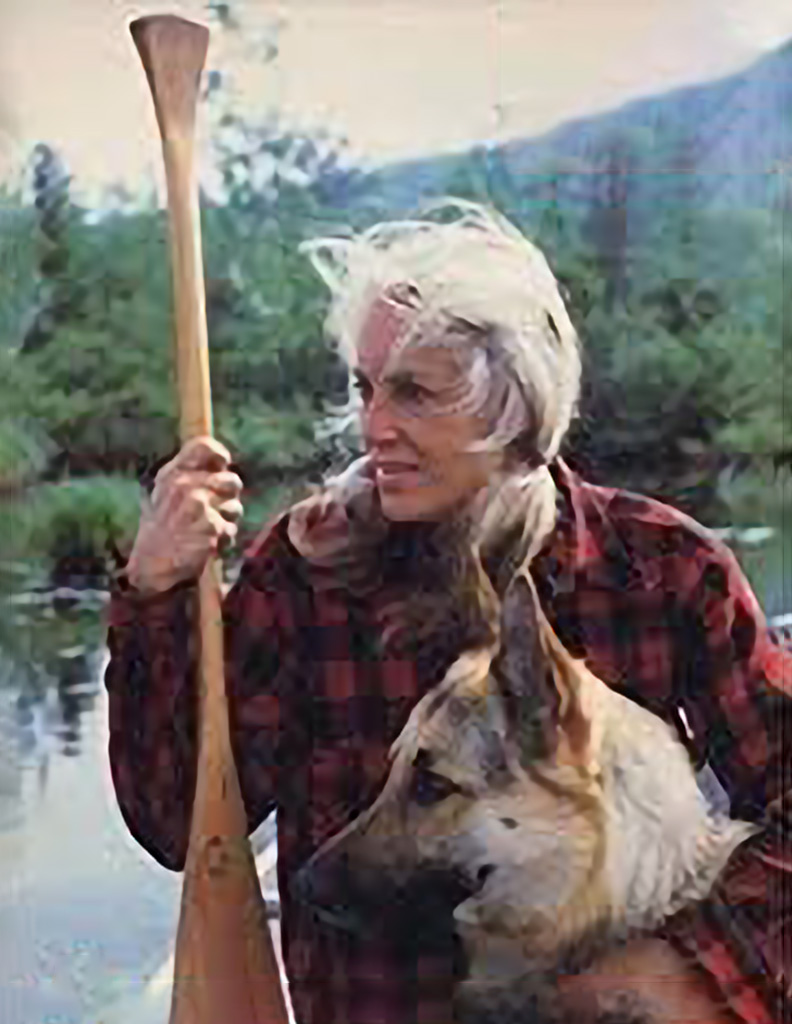

Anne LaBastille

Anne LaBastille was a woman who could have out-Thoreau-ed Thoreau himself. She built her influence through a successful writing career while living in a small cabin in a remote part of the Adirondack wilderness.

Her four-volume autobiographical series “Woodswoman”, published in 1976, has inspired decades of women to get outdoors and enjoy self-sufficient pursuits like hunting and fishing. And her 1980 book “Women and the Wilderness” addressed the historically male-dominated culture of conservation and put a spotlight on female naturalists.

A licensed wilderness guide, this Cornell graduate was also a consummate defender of the Adirondacks and served as commissioner of the Adirondack Park Agency from 1975 to 1993.

Mollie H. Beattie

Appointed as the first female director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1993 by President Clinton, Beattie fiercely opposed the dismantling and defunding of the Endangered Species Act and Clean Water Act in Congress. She was a forester by training and put great emphasis on managing habitat and the economy by stressing the responsibility of private landowners to effectively steward forest lands.

Unfortunately, her tenure with the Service was cut short by a fatal brain tumor, but not before she oversaw the establishment of 15 national wildlife refuges, the signing of more than 100 habitat conservation plans with private landowners, and the reintroduction of the gray wolf into the northern Rocky Mountains.

Lisa P. Jackson

Jackson started her career at the Environmental Protection Agency as a staff-level scientist before working her way up to the position of Administrator over the course of her career. The fourth woman and first Black American to hold the position, Jackson has spearheaded environmental programs to protect clean water, reduce harmful emissions, and protect at-risk communities.

Jackson eventually left the EPA to join Apple Inc. and now serves as the tech company’s vice president of Environmental Policy and Social Initiatives. She oversees efforts to minimize environmental impacts of business and address climate change through renewable energy and green materials.

Rue Mapp

After growing up in an outdoor-loving family, an adult Mapp was surprised to find that she was the only African American woman in her hiking groups and bike trips. Determined to get more members of her community involved in the outdoors, Mapp founded Outdoor Afro, a nonprofit organization dedicated to connecting Black Americans with outdoor spaces. Mapp’s goal is to shift the visual representation of what getting out into nature in America looks like and provide outdoor leadership training for people of color.

Her work has successfully connected underrepresented communities to nature and the benefits of spending more time outdoors. She currently serves on the boards of the Outdoor Industry Association the Wilderness Society, helping to shape conservation initiatives. She has also been named a National Geographic fellow.

Click HERE for the full post by Cory Deal on the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership website.