On April 17 Arizona Game and Fish Department, with help from Arizona Trout Unlimited, tried a new stocking technique and planted Gila Trout eggs in Grapevine and Frye Creeks near Prescott. As of the end of May, of the approximately 19,000 Gila Trout eggs planted in Grapevine Creek the representatives returned to determine the survival rate. They found hundreds of 20-30 mm Gila Trout in each of the pools that were stocked with eggs and even in a few pools where eggs were not stocked. The success rate will continue to be monitored through the summer and the following years.

Arizona Game and Fish Department Successfully Plants Gila Trout Eggs Into Frye Creek!

Praising Arizona

How the shutdown is harming anglers

“Good riddance. Think of all of the money we are saving.”

I looked at Max in exasperation. He is one of the most hard-core sportsmen I know. I have hunted for whitetail with him in driving rainstorms in West Virginia, and stalked catfish on the Potomac using hummus-impregnated Clouser-minnows. He is a tremendous conservationist, and every year donates enough money to be a member of Trout Unlimited’s Griffith Circle.

He is also a big believer in small government. Max and I rarely talk politics, and the partial shutdown of the federal government is all about politics.

Sportsmen such as Max should be most outraged by the fact that our natural resource agency partners in the federal government are at home instead of at their desks or in the field. I spent the first 10 years of my career working for the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service, and almost every employee I met began their career from the same starting point. They wanted to make the world a better place.

And they do. The shutdown means that we cannot work with Bart Gamett, a Forest Service biologist on Idaho’s Yankee Fork, a historically important spawning and rearing tributary of the Salmon River. We worked with Bart and an array of other partners to restore the stream. Juvenile trout and salmon immediately occupied the restored section. A father who was camping with his young son, turned to him and said, “These people are doing this so that when you take your children camping here there will be salmon and steelhead to see.”

Our partnership with the BLM allowed us to identify Muddy Creek in Wyoming as a potential native fish conservation area. We worked with BLM to eliminate non-native brook trout and helped to restore Colorado River cutthroat trout. That spurred a partnership between the BLM and The Nature Conservancy to restore imperiled flannelmouth sucker, bluehead sucker, and roundtail chub downstream in the warm water reaches. It goes without saying that restoration efforts such as these ease the social and economic disruption to local communities caused by listing fish under the Endangered Species Act.

Without the support of a few U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employees, few would have guessed that recreational fishing of streams in the so-called Driftless Area of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and Illinois generates a whopping $1.6 billion in economic returns for the largely rural communities in the area. That fact certainly helped inspire the Natural Resource Conservation Service to invest over $9 million in restoration last year into the Driftless. The shutdown could slow our ability to work with NRCS employees such as Chad Dewrye to bring more landowners into the restoration program.

Sportsmen and women cannot spend their money in local communities if they cannot access the places they love to hunt and fish. Consider Fletcher’s Cove, a popular concession on the C and O Canal, a national park in Washington, D.C., managed by the Park Service. The combination of high water and the shutdown imperil access to the epic spring shad fishery. The Friends of Fletcher’s Cove and local TU Business Partners such as District Angler are taking action to organize volunteers to remove the debris, and re-open the access.

Our partnership with the federal natural resource agencies benefits everyone who loves to fish or cares about clean water. For example, we have about $35 million in active projects with our federal partners. We will leverage that into nearly $200 million in funding to reconnect more than 1,200 miles of river and restore another 600 — but not if the federal government stays closed.

Max won’t listen to me when I talk about this stuff. So, when the weather warms, I will take him down to West Virginia, and fish for native brookies on the Monongahela National Forest. I will check in with TU’s restoration staff first because I have seen the photos of the 15-inch native brookie they caught this year on one of the more than 30 miles of streams they restored on the “Mon.”

In the meantime, the rest of us who love to hunt and fish, should urge the President and the Congress to get our resource professionals back on the job so they can continue their good work of making the world a better place.

Chris Wood is the president and CEO of Trout Unlimited.

Biomass decision may save forest restoration efforts

The Arizona Corporation Commission this week agreed to require the state’s utilities to buy or produce 90 megawatts of energy annually from biomass — saving the forest restoration industry from collapse.

The Corporation Commission on a 4-1 vote ordered the reluctant staff to come up with a proposed set of rules to create a market for the 1.5 million tons of branches, brush and debris created by thinning 50,000 acres of overgrown forest annually.

“We were in a desperate situation,” said Gila County Supervisor Tommie Martin, a leading member of the stakeholders group for the Four Forest Restoration Initiative (4FRI). “This is critical.”

The ACC staff had drafted a report questioning the value of extending even the current mandates to buy 28 megawatts of power, much less expanding the requirement to 90 megawatts.

But Commissioner Andy Tobin led the push for the full 90 megawatt requirement, which would create the market needed to jump-start the moribund 4FRI effort. It could also boost the average homeowner’s electric bill by $1 to $4 a month, based on an earlier, still debated study by Arizona Public Service (APS).

“This is huge, absolutely huge,” said Martin of the provisional commission support for expanding the market for biomass. “It turns the biomass into a product instead of a problem. If we can’t figure out how to let the industry deal with these attendant issues, we’re not ever going to get this forest cleaned out — period.”

Novo Power President Brad Worsley said only a Corporation Commission mandate and long-term contracts from the Forest Service will make it possible to create the biomass power generation plants needed to sustain forest restoration. Novo Power operates a 28 megawatt biomass power plant in Snowflake, the only one in Arizona. APS currently has a four-year contract to buy power from the plant, which has sustained the forest restoration efforts in the White Mountains.

“I’m grateful for what happened Monday,” said Worsley. “But I’m not breathing a lot easier yet. It’s not done until it’s done — and it’s not done yet.”

The commission must still adopt a final rule, with many key details still unresolved.

Forest restoration advocates showed up in force this week at a commission hearing, prompting the commissioners to essentially overrule a staff report. The staff had concluded the commission should focus on keeping electric rates as low as possible instead of shifting the cost of forest restoration onto electricity users.

However, forest advocates pointed out that creating a market for millions of tons of biomass would benefit the entire state. Large-scale thinning would likely increase runoff from millions of acres of watershed into the Valley, in a state with a worsening water shortage. Saving the forest restoration efforts would also potentially save billions in wildfire suppression costs and billions in property damage. It will also save lives by reducing deaths from air pollution from wildfires, save the lives of firefighters and homeowners from megafires. All the while, the biomass industry will provide jobs in hard-pressed rural industries.

“Commissioner Tobin pointed out that rarely is a political movement pure in its intention and perfect in its answers — but there are very few things we work on at a state or national level more important,” said Worsley.

Martin said APS and other power companies also supported the plan, along with a host of environmental groups, officials from rural counties, logging companies and advocates for economic development.

“We now have an opportunity to see if the market can solve this problem — we didn’t have that before,” said Martin.

The Forest Service has struggled for a decade to find a contractor who could thin the millions of acres of overgrown forests, which have contributed to a massive increase in wildfires. The Paradise fire in California that killed 85 people, consumed 15,000 homes and inflicted $9 billion in damages demonstrating the potential for disaster in a drought-plagued, overgrown forest.

The Forest Service has pioneered how to complete massive environmental analysis, getting hundreds of thousand of acres approved for clearing in a single study. However, one contractor after another has failed to come anywhere near the 50,000-acres-per-year pace envisioned a decade ago. Even at that pace, it would take perhaps 40 years to work through the 2 million acres in need of thinning. Tree densities have increased from maybe 50 per acre to perhaps 800 per acres over much of that area, due to fire suppression, grazing and clear-cut logging.

Given the new streamlined Forest Service system, economics now represents the biggest challenge to 4FRI, the biggest forest restoration effort in the nation’s history. The region now has only a handful of mills that could handle trees in the 12- to 16-inch diameter range. But the much greater challenge lies in getting rid of the thickets of 6- to 8-inch trees, branches from the larger trees and brush.

Every acre thinned produces roughly 50 tons of material — equally divided between logs for the mills and biomass. Contractors’ promises to turn the biomass into jet fuel, compost, soil char or other exotic products have all fallen short — leaving only biomass burning as a market.

Martin said the power companies, loggers, environmentalists, local officials and fire officials made common cause before the commission this week.

“They had a chance to be statesmen, to display the leadership needed to get this over the finish line — to really get a grip on these vulnerable forests.”

She noted that the commission will meet again to adopt a final rule in the next one to three months.

Worsley said only the adoption of such a rule combined with a Forest Service contract guaranteeing a supply of biomass for the next 15 to 20 years will make this possible for companies like his to get the financing needed to build additional biomass power plants.

His company has estimated it would build a 50 megawatt power plant in about 20 months for roughly $100 million.

The APS study estimated a 30 megawatt biomass power plant could cost as much as $500 million.

Still, forest advocates this week celebrated a crucial victory.

Navajo County Supervisor Jason Whiting said, “It would appear the commission now understands how much this matters to Arizona and its citizens. A month ago, this was on its deathbed — but through numerous prayers and efforts from concerned citizens, leaders and elected officials we are now moving in the right direction.”

Biomass plants would protect Rim Country, White Mountains

Save the fund that has saved public lands for recreation and conservation

Congress allowed the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), America’s most effective conservation program to expire on Oct. 1. It’s hard to understand how a program that has strong bipartisan support and has provided over $235 million for outdoor recreation and conservation in Arizona was not reauthorized. Americans lose over $15 million weekly of funds that would be available for local community parks and the conservation of public lands. It’s time for Congress to permanently reauthorize the program and provide for full funding. The benefits of the LWCF program can be found in virtually every community in our state. Access and recreation opportunities have been enhanced at the Grand Canyon National Park, Saguaro National Park, Lake Mead Recreation Area, Coconino National Forest, Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge and the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area. Hundreds of additional recreation projects have occurred on our state and community parks in nearly every community in Arizona.

For more than 50 years, the LWCF has delivered on-the-ground conservation achievements to communities across our state. In particular, benefits to rural America and the small communities that depend upon the hunting, fishing and outdoor recreation economy for economic development depend on this key program. In addition, urban opportunities to get our youth outdoors will suffer significant losses without the reauthorization of the program. Outdoor recreation supports 210,000 jobs, generates $5.7 billion in wages and salaries and produces $1.4 billion in state and local tax revenues. Over 1.5 million people participate in hunting, fishing and wildlife watching in Arizona, and they contribute over $2.1 billion to the state’s economy.

LWCF is not funded by taxpayer dollars but from fees collected from offshore oil and gas extraction. Let’s not break the 50-year-old promise to the American people to invest a small portion of the royalties generated from offshore oil and gas drilling to enhance our national parks, state parks, community recreation programs, hunting and fishing access, trails and open spaces. Please thank Congressman Grijalva for his leadership on this key issue and contact your congressional representative asking for their support of the permanent reauthorization and funding for of the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

LWCF, Expired

On October 1, Congress allowed the Land and Water Conservation Fund to expire. Why does that matter? In Arizona alone, we’ll lose millions in federal funds for outdoor recreation and conservation. Our friends from Trout Unlimited shared a statement from Brad Powell, the president of the Arizona Wildlife Federation. We’re sharing it, in turn, here, along with the remainder of Trout Unlimited’s release.

“Its hard to understand how a program that has strong bipartisan support and has provided over $235 million for outdoor recreation and conservation in Arizona was not reauthorized,” Powell said. “Americans lose over $15 million weekly of funds that would be available for local community parks and the conservation of public lands. It’s time for Congress to permanently reauthorize the program and provide for full funding.”

The benefits of the LWCF program can be found in virtually every community in our state. Access and recreation opportunities have been enhanced at Grand Canyon National Park, Saguaro National Park, Lake Mead Recreation area, Coconino National Forest, Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge and the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area. Hundreds of additional recreation projects have occurred in our state and community parks in nearly every community in Arizona.

For more than 50 years, the LWCF has delivered on-the-ground conservation achievements to communities across our state. In particular, benefits to rural America and the small communities that depend upon the hunting, fishing and outdoor recreation economy for economic development depend on this key program. In addition, urban opportunities to get our youth outdoors will suffer significant losses without the reauthorization of the program. Outdoor recreation supports 210,000 jobs, generates $5.7 billion in wages and salaries and produces $1.4 billion in state and local tax revenues. More than 1.5 million people participate in hunting, fishing and wildlife watching in Arizona, and they contribute over $2.1 billion to the state’s economy.

LWCF is not funded by taxpayer dollars, but from fees collected from offshore oil and gas extraction. Let’s not break the 50-year-old promise to the American people to invest a small portion of these royalties to enhance our national parks, state parks, community recreation programs, hunting and fishing access, trails and open spaces. Please thank Congressman Raul Grijalva for his leadership on this key issue and contact your Congressional representative to ask for their support of the permanent reauthorization and funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

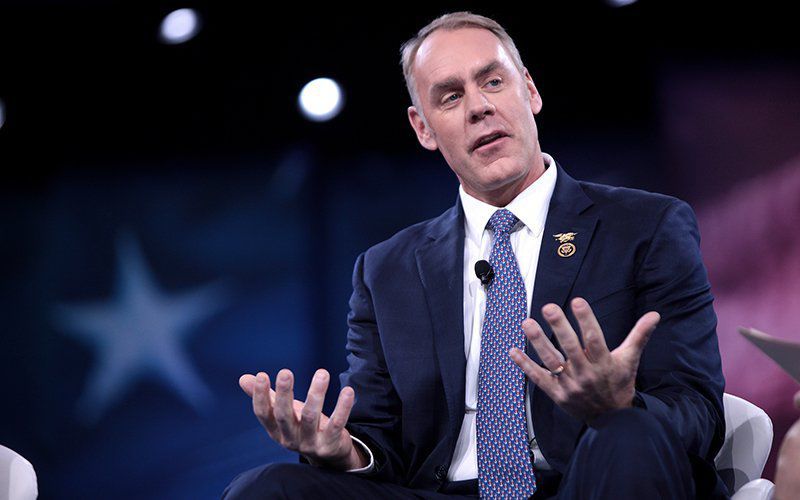

Zinke has ‘no intention’ of revisiting Grand Canyon uranium mining ban

WASHINGTON – Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has “no intention to revisit uranium mining” in and around the Grand Canyon, his spokeswoman said, after outdoorsmen’s groups launched a campaign urging him to keep a 20-year mining moratorium in place.

Advocates said they were worried the Trump administration was moving toward lifting a 2012 mining ban on 1 million acres of federal land around the canyon, but Zinke’s spokeswoman said in an email Monday that the secretary has no interest in doing that and “has made exactly zero moves to suggest otherwise.”

Mining opponents welcomed the news, but said Tuesday they still plan to be on their guard.

“People are behind protecting Grand Canyon, and I hope that citizens continue to make their voices heard, so that Department of Interior continues to protect this region, and so that the mining companies are aware of how important this place is to so many people,” said Alicyn Gitlin, conservation coordinator at the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club.

Scott Garlid said one of the first things that went through his head after hearing Zinke’s position was, “‘Good, we got their attention,’ because we’ve been asking this question and have gotten no response.”

Garlid is conservation director for the Arizona Wildlife Federation, one of two groups behind billboards that went up Monday in the Phoenix area, addressed to Zinke and urging him to “save the Grand Canyon from uranium mining.”

Then-Secretary Ken Salazar in 2012 imposed a 20-year moratorium on hard-rock mining, which includes uranium, on lands near the Grand Canyon. The moratorium was supposed to allow for further study of the environmental and health impacts of mining in the canyon region.

But mine opponents feared the Trump administration might be looking to lift the ban after uranium, in response to an executive order from President Donald Trump, was identified as one of 35 minerals critical to the nation’s security and economy. They also pointed to renewed calls from lawmakers, businesses and local government officials for the administration to review and possibly reverse “withdrawals” from mining imposed under the Obama administration.

That led to the billboards by the Arizona Wildlife Federation and the state chapter of Trout Unlimited.

But Zinke’s spokeswoman, Heather Swift, said the department was “disappointed to see such a tremendous waste of precious conservation dollars” by the groups.

“The Secretary has no intention to revisit uranium mining in and around the canyon and has made exactly zero moves to suggest otherwise,” she said in a statement Monday.

The advocates were pleased, but said the moratorium is just one thing needed for the region.

Rep. Tom O’Halleran, D-Sedona, said he wants to see a long-term commitment to a scientific study of the environmental and health impacts of uranium mining in the region.

“I am pleased to see the Department of Interior has decided to continue protecting and preserving the Grand Canyon Withdrawal Area and surrounding areas by not pursuing uranium mining in northern Arizona,” O’Halleran said Tuesday in an emailed statement.

“This mining and milling has had a lasting, toxic impact on the health of families and water and food quality throughout region. These communities cannot afford the impact continued mining would have,” he said.

Gitlin agreed, saying a major reason for that mining moratorium was “there was so much unknown about the effects of mining on the Grand Canyon region.”

“That science has largely been defunded, and so I would love to see the department say that they would be willing to actually fund the science and really learn about the region while we still have this mineral withdrawal in effect,” she said.

But O’Halleran said it’s time for Congress to act.

“We have an obligation to address the longstanding health issues created by this activity once and for all,” he said.

Garlid was not able to say Tuesday how much it cost to put up the billboards, which will be up for another two months. But he said it was money well-spent, saying they have already drawn a “fair amount of response.”

“We have added (about) 200 signatures in the last 24 hours,” Garlid said. “People are taking interest. It’s having the desired effect so far.”

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

Arizona could lose millions without federal grant program for outdoor recreation

APACHE JUNCTION – A federal fund that has brought millions of dollars to Arizona over the years for national parks, trail maintenance, even community swimming pools, expired Sept. 30. That could jeopardize future outdoor projects funded through the Land and Water Conservation Fund if Congress doesn’t act.

Lost Dutchman State Park, nestled at the base of the Superstition Mountains, is one of the places that has received grants from the fund to maintain trails. It’s where Richard Bruner, a retired Floridian, enjoys hiking.

“When you get higher up, you can hear the wind blow. When there’s nobody around, there’s no sounds. There’s nothing like that.”

In Arizona, which relies heavily on tourism dollars to boost its economy, the Land and Water Conservation Fund has been a windfall for cash-strapped recreational areas, giving more than $830,000 to Lost Dutchman and about $235 million to the state over the past 53 years, according to the Land and Water Conservation Fund Coalition.

Where the fund stands

Congress established the Land and Water Conservation Fund in 1965. Money from the fund, which comes from the revenue from offshore drilling for oil and natural gas, goes toward such uses as state and national parks, swimming pools and community centers.

Historically, the fund had bipartisan support because taxpayer dollars aren’t used. But because the National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Department can dip into the fund to purchase property, some in Congress believe the program gives too much money to federal agencies and not enough to state and local governments.

Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, who chairs the House Natural Resources Committee, is one of those lawmakers. He wrote an op-ed piece in Politico after trying to kill the fund’s reauthorization in 2015, citing “fundamental flaws” in the way the fund operates.

“Because states know best the needs of the people in their communities, the original 1965 law required that states receive the lion’s share of funding from the (Land and Water Conservation Fund),” Bishop wrote. “Unfortunately, the stateside program has been gradually crowded out over the years by the federal government’s powerful drive to acquire more and more land.”

But in mid-September, Bishop cut a surprise deal with Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Tucson, who had in 2017 proposed a bill to permanently reauthorize the fund. Their deal requires 40 percent of the fund to go to individual states and another 40 percent to the federal government, with the rest available for state and federal projects.

Bishop said the compromise isn’t perfect, but he called it an improvement over previous versions of the fund, which focused money on land acquisition by the federal government.

Grijalva said he supports the fund because of its broad reach and ability to bring the outdoors to people who may not be able to get out of the city. Cities across Arizona use fund money to maintain parks and other recreational areas.

“The state doesn’t have the money,” Grijalva said. “Local cities and communities are barely keeping up with the demands they have, and so there’s no supplement for them.”

The House Natural Resource Committee passed Grijalva’s bill, but it still has to be approved by Congress.

Nathan Rees, the Arizona coordinator for the wildlife advocacy group Trout Unlimited, and other conservationists were optimistic Congress would act before the Sunday deadline.The federal government will continue to collect revenue from oil and gas production even though the fund has expired. The money will be pooled in a general fund available to other congressional programs.

“Projects that are already in the pipeline to receive (Land and Water Conservation Fund) funding, they’ll get that funding,” Rees said. “But anything in the future isn’t going to receive any (fund) dollars. The money just gets siphoned right into the Treasury and who knows what happens then. It’s as good as gone.”

What the dollars mean in Arizona

Projects in Arizona have received about $235 million from the Land and Water Conservation Fund over the past 53 years, according to the Land and Water Conservation Fund Coalition. In addition to maintaining state parks like Lost Dutchman, it funded community pools like the Palo Verde Swimming Pool in Tucson, which received $29,000 in 1966, and the Tempe Sports Complex, which got $500,000 in 2002.

On Sept. 18 , Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke announced that Arizona would receive $2 million from the fund for recreation and conservation projects identified by the state.

Arizona government organizations use the funds in a variety of ways, said Meagan Fitzgerald with the Arizona Wildlife Federation, a group dedicated to protecting wildlife habitats.

“It’s helped protect places like the Grand Canyon National Park, the Saguaro National Park, Lake Mead Recreation Area,” she said. “They’ve even helped with keeping the lights on at some recreation parks.”

The broad appeal of the fund

At Eldorado Park in Scottsdale, Rees pointed to the lake, a defining feature of the park. It was constructed in 1972 using about $73,000 from the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Stocked every few months with sunfish, trout and catfish, the lake provides a fishing spot nestled in the city.

“(The fund) really just gets its fingers into every aspect of the community and can really appeal to everyone,” Rees said. “We’ve had the opportunity to hunt and fish and recreate in all these great outdoor spaces, and we want our kids and our grandkids to experience that same thing.”

Garett Reppenhagen, who served in the U.S. Army as a cavalry/scout sniper in the 1st Infantry Division in Iraq, knows this well.